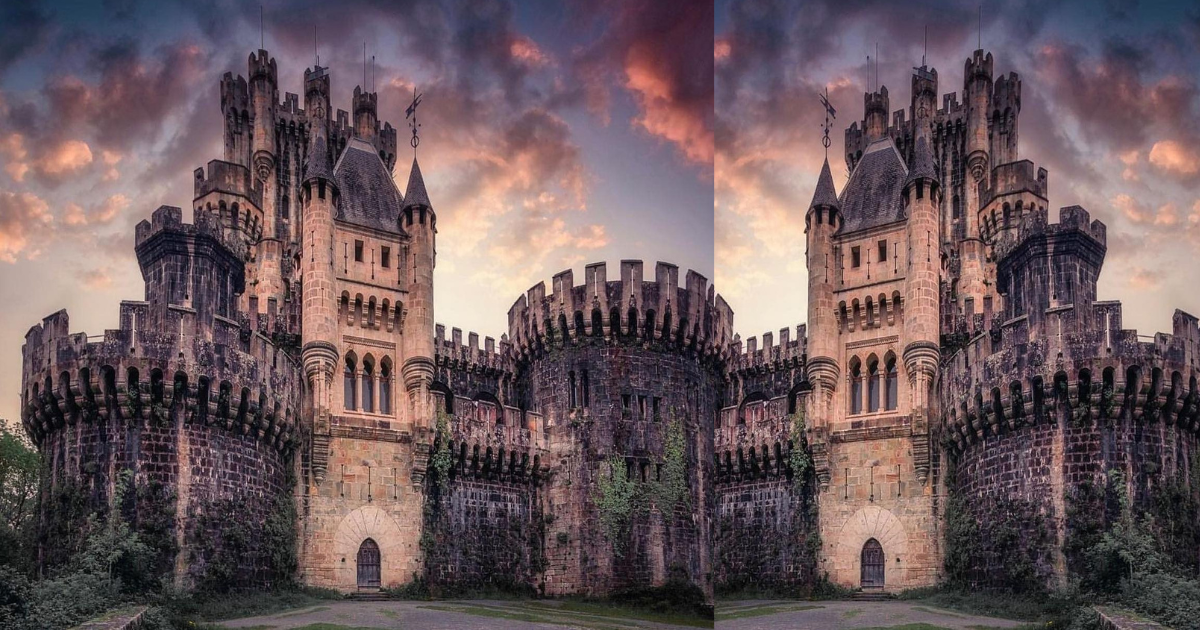

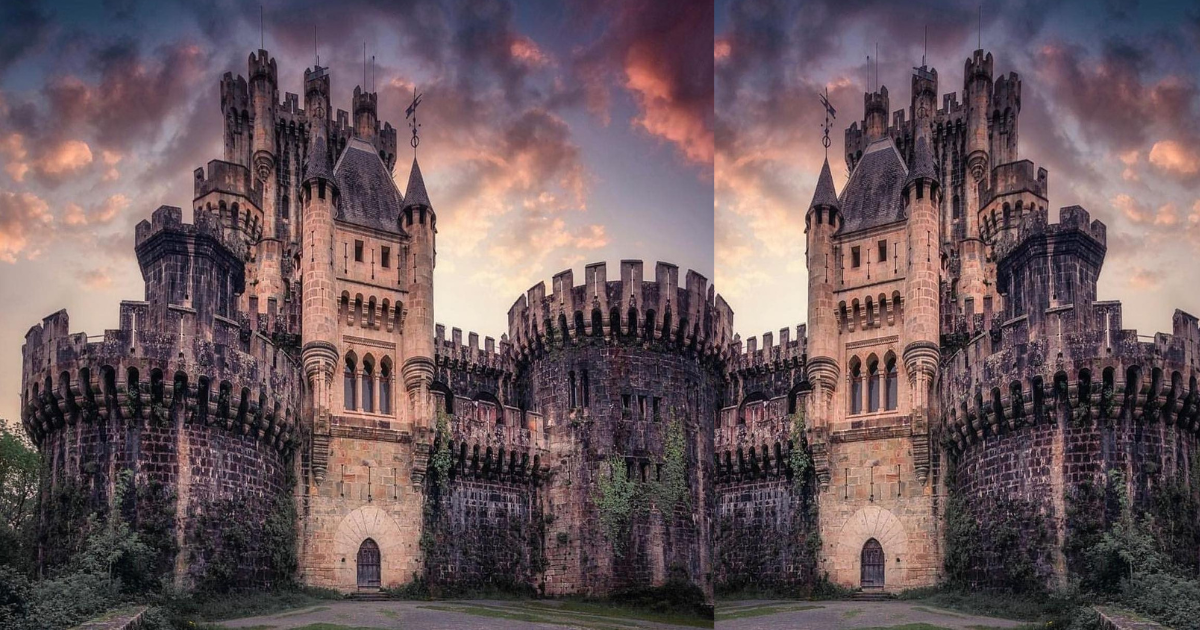

The castles of Ludwig II of Bavaria, the Crazy King, were designed to appear as if they were from a fantastic narrative. The monarch existed somewhere between myth and reality. As a result, he left prints such as those of Linderhof Palace. Locations given to story, landscapes chosen by authors linked with Germany, such as John Le Carré. But, a very comparable area is considerably closer. It’s in Bizkaia and has a similar storybook aura. It is the castle of Butrón, which evolved from a medieval fortification to the aesthetic mash-up that it is now in the nineteenth century.

The bloody past of Butrón Castle

The history of the tower-house that gave rise to Butrón Castle is a little murky. Tradition dates the initial building to the 8th century and is associated with the family and the river that gives it its name. It would have been erected by a knight, Captain Gamniz. Yet, this sort of structure first appeared during the 14th century. There was most likely a Butrón dwelling there before the Butron dynasty established at the beginning of the 13th century.

Descendants of the Haro, lords of Bizkaia, and eventually half of Europe’s royal families were heavily involved in the Bandos Wars. From the 13th through the 15th centuries, these battles wreaked havoc on the Basque regions. The Oacinos and the Gambonos were two opposing factions. Butrón opted for the former. Across the region, the atmosphere was terrible during those years.

Nobles on one side fought each other under nearly any excuse. People were regularly killed for being in the incorrect spot in the center. Thankfully, the majority of the time, the eruptions were restricted to brawls rather than fights. A backdrop reminiscent of mafia conflicts in which each faction attempted to seize economic and social dominance in the Basque Country.

All of this became the germ for the Brotherhoods, which became the foundation of the Provincial Councils. These entities made it feasible for the nobility to intervene. Nonetheless, from tower homes like Butrón, the banderizos had a solid position. In this case, it was a strong structure with solid walls. It has one of the most major forge complexes in Bizkaia. Ultimately, with the Spanish involvement in the mid-15th century to put a stop to the increasingly uncontrollable combat, the area was repurposed as a manor residence.

From tower-house to romantic castle

The Butrons were incorporated, and eventually diluted, into the Spanish aristocratic structure for generations. They were a prominent family who remained active until the 18th century. Plentzia was their primary source of power. It should also be mentioned that its name is most likely derived from the fishing equipment seen on its coat of arms.

The medieval fortification was in the hands of the 7th Marquis de la Torrecilla by the middle of the 19th century. It was him, Narciso de Salabert y Pinedo, who chose to give the then-ruined complex new life. To do so, he took the money that his Biscayan holdings had given him. Francisco de Cubas, another of his time’s most known architects. While he was most known as the mayor of Madrid and the architect of the Almudena Cathedral, he also designed Butrón Castle.

Although medieval components were included, the overall layout devised by the Marquis of Cubas was vastly different. The neo-Gothic style predominated, with an amalgamation influenced by the center and north of Europe to Spanish cities such as Segovia and its Alcazar. The weird structure began to take shape gradually.

In each corner, four formidable bastions mark the floor plan. They are round and powerful, and they stand out against the keep and the front facade. They are more complex, with spikes and holes, and have a storybook aspect. The watchtowers appear to be piling up. Another evidence of identity is that the areas are frequently connected in ways that are more beautiful than functional, such as by outdoor corridors. As a result, it is apparent that the palace was designed to be aesthetically pleasing rather than functional.

The abandonment of Butrón Castle

The dominance of the form made the building’s habitability relatively challenging. It functioned as a dwelling, although it was not as cozy as a typical one. Some towers, for example, had four-meter-high walls that created narrow, difficult-to-access compartments. Its undeniable appeal made it a location to be seen, yet it lacked a clear proprietor.

Over the twentieth century, it traveled through many owners until ending up in the hands of a commercial conglomerate. They’ve been attempting to sell it for years, but it’s now part of the municipality of Gatika. It was even put up for auction. Its last active duty, valued at several million euros and proclaimed a protected heritage, was to serve as a meeting and celebration venue until just after the millennium’s turn.

It has been abandoned since since. The black of the bastions is a wonderful illustration of this, as the stone used to make them is white. The massive garden surrounding it, where palm palms thrived, is also neglected.

Yet, the surrounding rich green emphasizes the magnificent picture of Butrón Castle. As a result, despite not being able to look inside, tourists continue to visit. Its position facilitates this, since the A-8 provides easy access to the local roads that lead to the property. Similarly, it is located between Bilbao’s city and Bermeo. As a result, San Juan de Gaztelugatxe is also nearby.

The above-mentioned maritime Plentzia provides access to the Cantabrian Sea. You may take a 14-kilometer-long and rather easy circular route between the two places. A way to appreciate the environment that typifies the Basque coast’s ecology between sea and mountains. A walk between the castle and Gatika, a little interior village with a lot of beauty, is also worthwhile.